Лимонную кислоту получают с помощью кишечной палочки

“E330” redirects here. For the locomotive, see FS Class E330.

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name Citric acid[1] | |||

| Systematic IUPAC name 2-Hydroxypropane-1,2,3-tricarboxylic acid | |||

| Identifiers | |||

CAS Number |

| ||

3D model (JSmol) |

| ||

| ChEBI |

| ||

| ChEMBL |

| ||

| ChemSpider |

| ||

| DrugBank |

| ||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.973 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| E number | E330 (antioxidants, …) | ||

IUPHAR/BPS |

| ||

| KEGG |

| ||

PubChem CID |

| ||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII |

| ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

| ||

InChI

| |||

SMILES

| |||

| Properties | |||

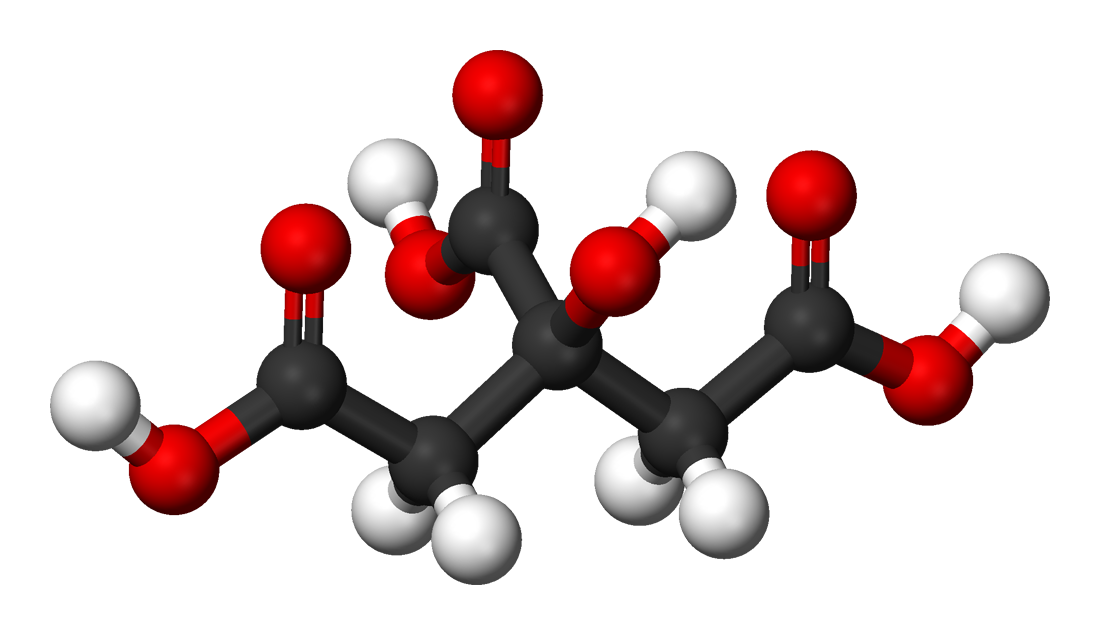

Chemical formula | C6H8O7 | ||

| Molar mass | 192.123 g/mol (anhydrous), 210.14 g/mol (monohydrate)[2] | ||

| Appearance | white solid | ||

| Odor | Odorless | ||

| Density | 1.665 g/cm3 (anhydrous) 1.542 g/cm3 (18 °C, monohydrate) | ||

| Melting point | 156 °C (313 °F; 429 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 310 °C (590 °F; 583 K) decomposes from 175 °C[3] | ||

Solubility in water | 54% w/w (10 °C) 59.2% w/w (20 °C) 64.3% w/w (30 °C) 68.6% w/w (40 °C) 70.9% w/w (50 °C) 73.5% w/w (60 °C) 76.2% w/w (70 °C) 78.8% w/w (80 °C) 81.4% w/w (90 °C) 84% w/w (100 °C)[4] | ||

| Solubility | Soluble in acetone, alcohol, ether, ethyl acetate, DMSO Insoluble in C 6H 6, CHCl3, CS2, toluene[3] | ||

| Solubility in ethanol | 62 g/100 g (25 °C)[3] | ||

| Solubility in amyl acetate | 4.41 g/100 g (25 °C)[3] | ||

| Solubility in diethyl ether | 1.05 g/100 g (25 °C)[3] | ||

| Solubility in 1,4-Dioxane | 35.9 g/100 g (25 °C)[3] | ||

| log P | −1.64 | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | pKa1 = 3.13[5] pKa2 = 4.76[5] pKa3 = 6.39,[6] 6.40[7] | ||

Refractive index (nD) | 1.493–1.509 (20 °C)[4] 1.46 (150 °C)[3] | ||

| Viscosity | 6.5 cP (50% aq. sol.)[4] | ||

| Structure | |||

Crystal structure | Monoclinic | ||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Heat capacity (C) | 226.51 J/(mol·K) (26.85 °C)[8] | ||

Std molar | 252.1 J/(mol·K)[8] | ||

Std enthalpy of | −1543.8 kJ/mol[4] | ||

Heat of combustion, higher value (HHV) | 1985.3 kJ/mol (474.5 kcal/mol, 2.47 kcal/g),[4] 1960.6 kJ/mol[8] 1972.34 kJ/mol (471.4 kcal/mol, 2.24 kcal/g) (monohydrate)[4] | ||

| Pharmacology | |||

ATC code | A09AB04 (WHO) | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Main hazards | Skin and eye irritant | ||

| Safety data sheet | HMDB | ||

| GHS pictograms | [5] | ||

| GHS Signal word | Warning | ||

GHS hazard statements | H319[5] | ||

GHS precautionary statements | P305+351+338[5] | ||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1 2 | ||

| Flash point | 155 °C (311 °F; 428 K) | ||

Autoignition | 345 °C (653 °F; 618 K) | ||

| Explosive limits | 8%[5] | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose) | 3000 mg/kg (rats, oral) | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| verify (what is ?) | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Citric acid is a weak organic acid that has the molecular formula C6H8O7. It occurs naturally in citrus fruits. In biochemistry, it is an intermediate in the citric acid cycle, which occurs in the metabolism of all aerobic organisms.

More than two million tons of citric acid are manufactured every year. It is used widely as an acidifier, as a flavoring and a chelating agent.[9]

A citrate is a derivative of citric acid; that is, the salts, esters, and the polyatomic anion found in solution. An example of the former, a salt is trisodium citrate; an ester is triethyl citrate. When part of a salt, the formula of the citrate anion is written as C

6H

5O3−

7 or C

3H

5O(COO)3−

3.

Natural occurrence and industrial production[edit]

Lemons, oranges, limes, and other citrus fruits possess high concentrations of citric acid

Citric acid exists in a variety of fruits and vegetables, most notably citrus fruits. Lemons and limes have particularly high concentrations of the acid; it can constitute as much as 8% of the dry weight of these fruits (about 47 g/l in the juices[10]).[a] The concentrations of citric acid in citrus fruits range from 0.005 mol/L for oranges and grapefruits to 0.30 mol/L in lemons and limes; these values vary within species depending upon the cultivar and the circumstances in which the fruit was grown.

Citric acid was first isolated in 1784 by the chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele, who crystallized it from lemon juice.[11][12]

Industrial-scale citric acid production first began in 1890 based on the Italian citrus fruit industry, where the juice was treated with hydrated lime (calcium hydroxide) to precipitate calcium citrate, which was isolated and converted back to the acid using diluted sulfuric acid.[13] In 1893, C. Wehmer discovered Penicillium mold could produce citric acid from sugar. However, microbial production of citric acid did not become industrially important until World War I disrupted Italian citrus exports.

In 1917, American food chemist James Currie discovered certain strains of the mold Aspergillus niger could be efficient citric acid producers, and the pharmaceutical company Pfizer began industrial-level production using this technique two years later, followed by Citrique Belge in 1929.

In this production technique, which is still the major industrial route to citric acid used today, cultures of A. niger are fed on a sucrose or glucose-containing medium to produce citric acid. The source of sugar is corn steep liquor, molasses, hydrolyzed corn starch, or other inexpensive, sugary solution.[14] After the mold is filtered out of the resulting solution, citric acid is isolated by precipitating it with calcium hydroxide to yield calcium citrate salt, from which citric acid is regenerated by treatment with sulfuric acid, as in the direct extraction from citrus fruit juice.

In 1977, a patent was granted to Lever Brothers for the chemical synthesis of citric acid starting either from aconitic or isocitrate/alloisocitrate calcium salts under high pressure conditions; this produced citric acid in near quantitative conversion under what appeared to be a reverse, non-enzymatic Krebs cycle reaction.[15]

Global production was in excess of 2,000,000 tons in 2018.[16] More than 50% of this volume was produced in China. More than 50% was used as an acidity regulator in beverages, some 20% in other food applications, 20% for detergent applications, and 10% for applications other than food, such as cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and in the chemical industry.[13]

Chemical characteristics[edit]

Speciation diagram for a 10-millimolar solution of citric acid

Citric acid can be obtained as an anhydrous (water-free) form or as a monohydrate. The anhydrous form crystallizes from hot water, while the monohydrate forms when citric acid is crystallized from cold water. The monohydrate can be converted to the anhydrous form at about 78 °C. Citric acid also dissolves in absolute (anhydrous) ethanol (76 parts of citric acid per 100 parts of ethanol) at 15 °C. It decomposes with loss of carbon dioxide above about 175 °C.

Citric acid is a tribasic acid, with pKa values, extrapolated to zero ionic strength, of 2.92, 4.28, and 5.21 at 25 °C.[17] The pKa of the hydroxyl group has been found, by means of 13C NMR spectroscopy, to be 14.4.[18]

The speciation diagram shows that solutions of citric acid are buffer solutions between about pH 2 and pH 8. In biological systems around pH 7, the two species present are the citrate ion and mono-hydrogen citrate ion. The SSC 20X hybridization buffer is an example in common use.[19] Tables compiled for biochemical studies[20] are available.

On the other hand, the pH of a 1 mM solution of citric acid will be about 3.2. The pH of fruit juices from citrus fruits like oranges and lemons depends on the citric acid concentration, being lower for higher acid concentration and conversely.

Acid salts of citric acid can be prepared by careful adjustment of the pH before crystallizing the compound. See, for example, sodium citrate.

The citrate ion forms complexes with metallic cations. The stability constants for the formation of these complexes are quite large because of the chelate effect. Consequently, it forms complexes even with alkali metal cations. However, when a chelate complex is formed using all three carboxylate groups, the chelate rings have 7 and 8 members, which are generally less stable thermodynamically than smaller chelate rings. In consequence, the hydroxyl group can be deprotonated, forming part of a more stable 5-membered ring, as in ammonium ferric citrate, (NH

4)

5Fe(C

6H

4O

7)

2·2H

2O.[21]

Citric acid can be esterified at one or more of its three carboxylic acid groups to form any of a variety of mono-, di-, tri-, and mixed esters.[22]

Biochemistry[edit]

Citric acid cycle[edit]

Citrate is an intermediate in the TCA cycle (aka TriCarboxylic Acid cycle, or Krebs cycle, Szent-Györgyi), a central metabolic pathway for animals, plants, and bacteria. Citrate synthase catalyzes the condensation of oxaloacetate with acetyl CoA to form citrate. Citrate then acts as the substrate for aconitase and is converted into aconitic acid. The cycle ends with regeneration of oxaloacetate. This series of chemical reactions is the source of two-thirds of the food-derived energy in higher organisms. Hans Adolf Krebs received the 1953 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery.

Some bacteria (notably E. coli) can produce and consume citrate internally as part of their TCA cycle, but are unable to use it as food because they lack the enzymes required to import it into the cell. After tens of thousand of evolutions in a minimal glucose medium that also contained citrate during Richard Lenski’s Long-Term Evolution Experiment, a variant E. coli evolved with the ability to grow aerobically on citrate. Zachary Blount, a student of Lenski’s, and colleagues studied these “Cit+” E. coli[23][24] as a model for how novel traits evolve. They found evidence that, in this case, the innovation was caused by a rare duplication mutation due to the accumulation of several prior “potentiating” mutations, the identity and effects of which are still under study. The evolution of the Cit+ trait has been considered a notable example of the role of historical contingency in evolution.

Other biological roles[edit]

Citrate can be transported out of the mitochondria and into the cytoplasm, then broken down into acetyl-CoA for fatty acid synthesis, and into oxaloacetate. Citrate is a positive modulator of this conversion, and allosterically regulates the enzyme acetyl-CoA carboxylase, which is the regulating enzyme in the conversion of acetyl-CoA into malonyl-CoA (the commitment step in fatty acid synthesis). In short, citrate is transported into the cytoplasm, converted into acetyl CoA, which is then converted into malonyl CoA by acetyl CoA carboxylase, which is allosterically modulated by citrate.

High concentrations of cytosolic citrate can inhibit phosphofructokinase, the catalyst of a rate-limiting step of glycolysis. This effect is advantageous: high concentrations of citrate indicate that there is a large supply of biosynthetic precursor molecules, so there is no need for phosphofructokinase to continue to send molecules of its substrate, fructose 6-phosphate, into glycolysis. Citrate acts by augmenting the inhibitory effect of high concentrations of ATP, another sign that there is no need to carry out glycolysis.[25]

Citrate is a vital component of bone, helping to regulate the size of apatite crystals.[26]

Applications[edit]

Food and drink[edit]

Powdered citric acid being used to prepare lemon pepper seasoning

Because it is one of the stronger edible acids, the dominant use of citric acid is as a flavoring and preservative in food and beverages, especially soft drinks and candies.[13] Within the European Union it is denoted by E number E330. Citrate salts of various metals are used to deliver those minerals in a biologically available form in many dietary supplements. Citric acid has 247 kcal per 100 g.[27] In the United States the purity requirements for citric acid as a food additive are defined by the Food Chemicals Codex, which is published by the United States Pharmacopoeia (USP).

Citric acid can be added to ice cream as an emulsifying agent to keep fats from separating, to caramel to prevent sucrose crystallization, or in recipes in place of fresh lemon juice. Citric acid is used with sodium bicarbonate in a wide range of effervescent formulae, both for ingestion (e.g., powders and tablets) and for personal care (e.g., bath salts, bath bombs, and cleaning of grease). Citric acid sold in a dry powdered form is commonly sold in markets and groceries as “sour salt”, due to its physical resemblance to table salt. It has use in culinary applications, as an alternative to vinegar or lemon juice, where a pure acid is needed. Citric acid can be used in food coloring to balance the pH level of a normally basic dye.[citation needed]

Cleaning and chelating agent[edit]

Structure of an iron(III) citrate complex.[28][29]

Citric acid is an excellent chelating agent, binding metals by making them soluble. It is used to remove and discourage the buildup of limescale from boilers and evaporators.[13] It can be used to treat water, which makes it useful in improving the effectiveness of soaps and laundry detergents. By chelating the metals in hard water, it lets these cleaners produce foam and work better without need for water softening. Citric acid is the active ingredient in some bathroom and kitchen cleaning solutions. A solution with a six percent concentration of citric acid will remove hard water stains from glass without scrubbing. Citric acid can be used in shampoo to wash out wax and coloring from the hair. Illustrative of its chelating abilities, citric acid was the first successful eluant used for total ion-exchange separation of the lanthanides, during the Manhattan Project in the 1940s. In the 1950s, it was replaced by the far more efficient EDTA.

In industry, it is used to dissolve rust from steel and passivate stainless steels.[30]

Cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, dietary supplements, and foods[edit]

Citric acid is used as an acidulant in creams, gels, and liquids. Used in foods and dietary supplements, it may be classified as a processing aid if it was added for a technical or functional effect (e.g. acidulent, chelator, viscosifier, etc.). If it is still present in insignificant amounts, and the technical or functional effect is no longer present, it may be exempt from labeling <21 CFR §101.100(c)>.

Citric acid is an alpha hydroxy acid and is an active ingredient in chemical skin peels.[citation needed]

Citric acid is commonly used as a buffer to increase the solubility of brown heroin.[31]

Citric acid is used as one of the active ingredients in the production of facial tissues with antiviral properties.[32]

Other uses[edit]

The buffering properties of citrates are used to control pH in household cleaners and pharmaceuticals.

Citric acid is used as an odorless alternative to white vinegar for home dyeing with acid dyes.

Sodium citrate is a component of Benedict’s reagent, used for identification both qualitatively and quantitatively of reducing sugars.

Citric acid can be used as an alternative to nitric acid in passivation of stainless steel.[33]

Citric acid can be used as a lower-odor stop bath as part of the process for developing photographic film. Photographic developers are alkaline, so a mild acid is used to neutralize and stop their action quickly, but commonly used acetic acid leaves a strong vinegar odor in the darkroom.[34]

Citric acid/potassium-sodium citrate can be used as a blood acid regulator.

Soldering flux. Citric acid is an excellent soldering flux,[35] either dry or as a concentrated solution in water. It should be removed after soldering, especially with fine wires, as it is mildly corrosive. It dissolves and rinses quickly in hot water.

Synthesis of solid materials from small molecules[edit]

In materials science, the Citrate-gel method is a process similar to the sol-gel method, which is a method for producing solid materials from small molecules. During the synthetic process, metal salts or alkoxides are introduced into a citric acid solution. The formation of citric complexes is believed to balance the difference in individual behavior of ions in solution, which results in a better distribution of ions and prevents the separation of components at later process stages. The polycondensation of ethylene glycol and citric acid starts above 100 °С, resulting in polymer citrate gel formation.

Safety[edit]

Although a weak acid, exposure to pure citric acid can cause adverse effects. Inhalation may cause cough, shortness of breath, or sore throat. Over-ingestion may cause abdominal pain and sore throat. Exposure of concentrated solutions to skin and eyes can cause redness and pain.[36] Long-term or repeated consumption may cause erosion of tooth enamel.[36][37][38]

Compendial status[edit]

- British Pharmacopoeia[39]

- Japanese Pharmacopoeia[40]

See also[edit]

- The closely related acids isocitric acid, aconitic acid, and propane-1,2,3-tricarboxylic acid (tricarballylic acid, carballylic acid)

- Acids in wine

References[edit]

- ^ ChemSpider lists ‘citric acid’ as the expert-verified IUPAC name.

- ^ CID 22230 from PubChem

- ^ a b c d e f g “citric acid”. chemister.ru. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f CID 311 from PubChem

- ^ a b c d e f Fisher Scientific, Citric acid. Retrieved on 2014-06-02.

- ^

“Data for Biochemical Research”. ZirChrom Separations, Inc. Retrieved January 11, 2012. - ^

“Ionization Constants of Organic Acids”. Michigan State University. Retrieved January 11, 2012. - ^ a b c Citric acid in Linstrom, Peter J.; Mallard, William G. (eds.); NIST Chemistry WebBook, NIST Standard Reference Database Number 69, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg (MD), https://webbook.nist.gov (retrieved 2014-06-02)

- ^ Apleblat, Alexander (2014). Citric acid. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-11232-9.

- ^ Penniston KL, Nakada SY, Holmes RP, Assimos DG (2008). “Quantitative Assessment of Citric Acid in Lemon Juice, Lime Juice, and Commercially-Available Fruit Juice Products”. Journal of Endourology. 22 (3): 567–570. doi:10.1089/end.2007.0304. PMC 2637791. PMID 18290732.

- ^ Scheele, Carl Wilhelm (1784). “Anmärkning om Citron-saft, samt sätt at crystallisera densamma” [Note about lemon juice, as well as ways to crystallize it]. Kungliga Vetenskaps Academiens Nya Handlingar [New Proceedings of the Royal Academy of Science]. 2nd series (in Swedish). 5: 105–109.

- ^ Graham, Thomas (1842). Elements of chemistry, including the applications of the science in the arts. Hippolyte Baillière, foreign bookseller to the Royal College of Surgeons, and to the Royal Society, 219, Regent Street. p. 944. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Verhoff, Frank H.; Bauweleers, Hugo (2014). “Citric Acid”. Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a07_103.pub3.

- ^ Lotfy, Walid A.; Ghanem, Khaled M.; El-Helow, Ehab R. (2007). “Citric acid production by a novel Aspergillus niger isolate: II. Optimization of process parameters through statistical experimental designs”. Bioresource Technology. 98 (18): 3470–3477. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2006.11.032. PMID 17317159.

- ^ US 4056567-V.Lamberti and E.Gutierrez

- ^ “Global Citric Acid Markets Report, 2011-2018 & 2019-2024”. prnewswire.com. March 19, 2019. Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- ^

Goldberg, Robert N.; Kishore, Nand; Lennen, Rebecca M. (2002). “Thermodynamic Quantities for the Ionization Reactions of Buffers”. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 31 (1): 231–370. Bibcode:2002JPCRD..31..231G. doi:10.1063/1.1416902. S2CID 94614267. - ^ Silva, Andre M. N.; Kong, Xiaole; Hider, Robert C. (2009). “Determination of the pKa value of the hydroxyl group in the α-hydroxycarboxylates citrate, malate and lactate by 13C NMR: implications for metal coordination in biological systems”. Biometals. 22 (5): 771–778. doi:10.1007/s10534-009-9224-5. PMID 19288211. S2CID 11615864.

- ^ Maniatis, T.; Fritsch, E. F.; Sambrook, J. 1982. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- ^

Gomori, G. (1955). “16 Preparation of buffers for use in enzyme studies”. Methods in Enzymology Volume 1. Methods in Enzymology. 1. pp. 138–146. doi:10.1016/0076-6879(55)01020-3. ISBN 9780121818012. - ^ Matzapetakis, M.; Raptopoulou, C. P.; Tsohos, A.; Papaefthymiou, V.; Moon, S. N.; Salifoglou, A. (1998). “Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Structural Characterization of the First Mononuclear, Water Soluble Iron−Citrate Complex, (NH4)5Fe(C6H4O7)2·2H2O”. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120 (50): 13266–13267. doi:10.1021/ja9807035.

- ^ Bergeron, Raymond J.; Xin, Meiguo; Smith, Richard E.; Wollenweber, Markus; McManis, James S.; Ludin, Christian; Abboud, Khalil A. (1997). “Total synthesis of rhizoferrin, an iron chelator”. Tetrahedron. 53 (2): 427–434. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(96)01061-7.

- ^ Powell, Alvin (February 14, 2014). “59,000 generations of bacteria, plus freezer, yield startling results”. phys.org. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ Blount, Z. D.; Borland, C. Z.; Lenski, R. E. (June 4, 2008). “Historical contingency and the evolution of a key innovation in an experimental population of Escherichia coli” (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (23): 7899–7906. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.7899B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0803151105. PMC 2430337. PMID 18524956. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 21, 2016. Retrieved April 13, 2017.

- ^ Stryer, Lubert; Berg, Jeremy; Tymoczko, John (2003). “Section 16.2: The Glycolytic Pathway Is Tightly Controlled”. Biochemistry (5. ed., international ed., 3. printing ed.). New York: Freeman. ISBN 978-0716746843.

- ^ Hu, Y.-Y.; Rawal, A.; Schmidt-Rohr, K. (December 2010). “Strongly bound citrate stabilizes the apatite nanocrystals in bone”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (52): 22425–22429. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10722425H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1009219107. PMC 3012505. PMID 21127269.

- ^ Greenfield, Heather; Southgate, D.A.T. (2003). Food Composition Data: Production, Management and Use. Rome: FAO. p. 146. ISBN 9789251049495.

- ^ Xiang Hao, Yongge Wei, Shiwei Zhang (2001): “Synthesis, crystal structure and magnetic property of a binuclear iron(III) citrate complex”. Transition Metal Chemistry, volume 26, issue 4, pages 384–387. doi:10.1023/A:1011055306645

- ^ Shweky, Itzhak; Bino, Avi; Goldberg, David P.; Lippard, Stephen J. (1994). “Syntheses, Structures, and Magnetic Properties of Two Dinuclear Iron(III) Citrate Complexes”. Inorganic Chemistry. 33 (23): 5161–5162. doi:10.1021/ic00101a001.

- ^ “ASTM A967 / A967M – 17 Standard Specification for Chemical Passivation Treatments for Stainless Steel Parts”. www.astm.org.

- ^ Strang J, Keaney F, Butterworth G, Noble A, Best D (April 2001). “Different forms of heroin and their relationship to cook-up techniques: data on, and explanation of, use of lemon juice and other acids”. Subst Use Misuse. 36 (5): 573–88. doi:10.1081/ja-100103561. PMID 11419488. S2CID 8516420.

- ^ “Tissues that fight germs”. CNN. July 14, 2004. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- ^ “Pickling and Passivating Stainless Steel” (PDF). Euro-inox.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 12, 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-01.

- ^ Anchell, Steve. “The Darkroom Cookbook: 3rd Edition (Paperback)”. Focal Press. Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- ^ “An Investigation of the Chemistry of Citric Acid in Military Soldering Applications” (PDF). June 19, 1995.

- ^ a b “Citric acid”. International Chemical Safety Cards. NIOSH. September 18, 2018. Archived from the original on July 12, 2018. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- ^ J. Zheng; F. Xiao; L. M. Qian; Z. R. Zhou (December 2009). “Erosion behavior of human tooth enamel in citric acid solution”. Tribology International. 42 (11–12): 1558–1564. doi:10.1016/j.triboint.2008.12.008.

- ^ “Effect of Citric Acid on Tooth Enamel”.

- ^ British Pharmacopoeia Commission Secretariat (2009). “Index, BP 2009” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 11, 2009. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ^ “Japanese Pharmacopoeia, Fifteenth Edition” (PDF). 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 22, 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- ^ This still does not make the lemon particularly strongly acidic. This is because, as a weak acid, most of the acid molecules are not dissociated so not contributing to acidity inside the lemon or its juice.

Источник

Микроорганизмы в пищевых продуктах присутствуют всегда. Патогенные микроорганизмы могут быть уничтожены благодаря обработке продуктов. Они могут стремительно размножаться из-за неправильной транспортировки, хранения, приготовления, или подачи. Увеличение количества этих микроорганизмов может привести не только к порче пищи, но и вызвать серьёзное отравление. Распространённый представитель пищевых патогенных бактерий – кишечная палочка. Кишечная палочка является частью микрофлоры кишечника человека и животных.

Некоторые виды кишечных палочек – патогенные для человека, то есть способны вызвать заболевание.

Бактерии группы кишечной палочки – универсальный показатель качества пищевых продуктов. Наличие кишечной палочки – показатель фекального загрязнения, особенно воды.

К сожалению, по внешнему виду, запаху или вкусу мы не сможем сказать, загрязнена ли пища кишечной палочкой (E. coli).

Кишечной палочкой могут быть обсеменены многие продукты, включая говядину, зелень, готовые к употреблению салаты, фрукты, сырое молоко и сырое тесто, нарезки колбас, сыров , особенно в условиях рынка, где не всегда обрабатывается аппарат для нарезки, мясорубки для приготовления фарша. Кишечная палочка активно размножается во время гниения продуктов.

Механизм передачи возбудителя фокально-оральный. Заражение происходит через пищу, воду, грязные руки.

Эта бактерия способна вырабатывать токсины (25 типов) и в зависимости от типа токсина, вырабатываемого кишечной палочкой, она обладают определенным действием.

Например, энтеротоксигенные E.coli имеют высокомолекулярный термолабильный токсин, который действует аналогично холерному, вызывая холероподобную диарею (гастроэнтериты у детей младшего возраста, диарею путешественников и др.).

Энтероинвазивные кишечные палочки вызывают профузную диарею с примесью крови и большим количеством лейкоцитов (аналогично дизентерие).

Энтеропатогенные E.coli вызыают водянистую диарею и выраженное обезвоживание.

Энтерогеморрагические кишечные палочки вызывают диарею с примесью крови.

Симптомы

Симптомы пищевого отравления отравления кишечной палочкой: боль в животе, тошнота, рвота, диарея более 20 раз в сутки, возможно с кровью. Температура тела обычно повышается незначительно или остаётся в норме.

Кишечная палочка является наиболее распространенным патогеном, вызывающим менингит у новорождённых детей. Он имеет высокие показатели заболеваемости и смертности во всем мире.

В группе риска

-Взрослые в возрасте 65 лет и старше

-Дети младше 5 лет

-Люди с ослабленной иммунной системой, в том числе беременные

-Люди, которые путешествуют в определенные страны

Профилактика

Чтобы защитить себя от инфекций, вызванных кишечной палочкой, а также от других болезней пищевого происхождения, соблюдайте основные правила безопасности:

-Мойте руки, посуду и кухонные поверхности горячей мыльной водой до и после приготовления или приема пищи.

– Используйте отдельные разделочные доски для сырых продуктов и готовых

-Тщательно мойте фрукты и овощи, испотльзуйте щетку для овощей.

-Держите сырые продукты, особенно мясо и птицу, отдельно от готовых к употреблению продуктов.

– Охлаждайте или замораживайте скоропортящиеся продукты как можно быстрее.

– Избегайте непастеризованных соков, молочных продуктов.

– Не ешьте сырое тесто.

– Пейте бутилированную воду.

-Тщательно прожаривайте мясо.

Источник

Escherichia coli – кишечная палочка – в основном безвредная бактерия, являющаяся частью физиологической кишечной флоры людей и животных. К сожалению, некоторые виды бактерий способны вызывать заболевания.

Обычно это желудочно-кишечные инфекции, проявляющиеся как диарея, инфекции мочевыводящих путей или менингит. При благоприятных условиях кишечная палочка может вызывать инфекцию других органов, в том числе желчных протоков или дыхательной системы.

Это также наиболее распространенный этиологический фактор при внутрибольничных инфекциях. Escherichia coli часто поражает людей с тяжелыми сопутствующими заболеваниями, в том числе с сахарным диабетом, алкоголизмом, хронической обструктивной болезнью легких.

Кишечная палочка также является маркером загрязнения питьевой воды путем выявления так называемых титров Escherichia coli. Штаммы, вызывающие диарею, передаются через загрязненную воду, пищу или через прямой контакт с инфицированными людьми или животными. Escherichia coli также является наиболее распространенным этиологическим фактором диареи путешественников.

Escherichia coli

Патогенные кишечные палочки

Среди штаммов Escherichia coli были выделены следующие: патогенные кишечные палочки, которые могут вызывать тяжелые инфекции:

- Entero Escherichia coli (Enterohemorrhagic E. coli – EHEC). Иначе: Escherichia coli, продуцирующая токсин Shiga (анг. Shiga toxin, STEC ) или Escherichia coli, продуцирующая werocytotoksynę (анг. Verocytotoxin, VTEC ). Наиболее известная и самая распространенная бактерия в этой группе – Escherichia coli O157: H7. Энтерогеморрагические штаммы кишечной палочки встречаются в пищеварительном тракте жвачных животных (КРС, козы, овцы, олени, лоси), свиней и птиц. Все они могут распространять бактерии. Наиболее распространенные источники заражения людей – крупный рогатый скот, употребление загрязненной воды, сырое или недоваренное мясо, непастеризованное молоко или молочные продукты, прямой контакт с животными или фекалиями больных людей, например, при смене подгузников.

- Энтеротоксигенная кишечная палочка (Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli – ETEC). Является основной причиной «диареи путешественников». Вырабатывает энтеротоксин, поражающий клетки слизистой оболочки тонкого кишечника, вызывая выделение большого количества воды в просвет кишечника.

- Энтеропатогенная кишечная палочка (Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli – EPEC) Распространенный этиологический агент диареи у детей.

- Enteroagregacyjna Escherichia coli (Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli – EAggEC). Вызывает хроническую диарею у детей в развивающихся странах. Это также этиологический фактор в 30% случаев «диареи путешественников». В 2011 году мутант этого штамма, способный продуцировать токсин шига – O104: H4, вызвал эпидемию в Германии. У 22% из зараженных развился гемолитический уремический синдром. Источником бактерий оказались семена пажитника, импортированные из Египта.

- Enteroinwazyjna Escherichia coli (Enteroinvasive Escherichia coli – EIEC). Вызывает бактериальную дизентерию.

- Adherencyjna Escherichia coli (Диффузно адгезивная Escherichia coli – DAEC). Вызывает хроническую диарею у детей.

- Штаммы Escherichia coli, содержащие антиген K1. Вызывают менингит у новорожденных. Инфекция у взрослых обычно является осложнением нейрохирургических операций или повреждений центральной нервной системы.

- Уропатогенная кишечная палочка. Этиологический фактор инфекции мочевыводящих путей, пиелонефрита, острого простатита, а также инфекции крови в виде уросепсиса. Бактерии, принадлежащие к этому штамму, имеют особенность, позволяяющую им соединяться с клетками, выстилающими мочевыводящие пути. Инфекция мочевого пузыря особенно распространена у взрослых женщин. Также увеличивает риск инфекции наличие гипертрофии простаты или катетера мочевого пузыря.

Как часто возникают инфекции толстой кишки

Данные по странам различаются, но тенденция к увеличению таких инфекций сохраняется.

Например, по данным Национального института гигиены, в Польше ежегодно насчитывается около 400-500 диарей-формирующих инфекций Escherichia coli, несколько случаев энтерогоррагических инфекций Escherichia coli и несколько случаев гемолитического уремического синдрома А в Соединенных Штатах ежегодно диагностируется более 260000 случаев энтерогеморрагической инфекции кишечной палочки, включая 36% штамма O157: H7, который вызывает серьезные осложнения.

В каждой европейской стране ежегодно обнаруживается несколько десятков случаев менингита и сепсиса, вызванных штаммом K1 Escherichia coli. По оценкам специалистов, около 50% женщин испытывают по крайней мере один эпизод инфекции мочевыводящих путей, вызванной уропатогенной кишечной палочкой. Это также ведущий этиологический фактор при внутрибольничных инфекциях.

Частота возникновения других инфекций, вызванных кишечной палочкой, неизвестна, поскольку отдельная статистика по ним практически не ведется.

Как проявляются инфекции, связанные с кишечной палочкой

Симптомы заражения энтерогеморрагической кишечной палочкой:

- Инкубационный период заболевания составляет от 1 до 10 дней, обычно 3-4 дня. Первым симптомом является диарея, часто с примесью свежей крови, спазмы в животе, рвота, умеренная температура. Симптомы длятся в среднем 5-7 дней.

- У 5-10% пациентов, обычно через 7 дней, когда проходит диарея, развивается опасное для жизни осложнение, т.е. гемолитический уремический синдром, включающий повреждение почек, проявляющийся как уменьшение или прекращение мочеиспускания и разрушение эритроцитов, приводящее к анемии, проявляющаяся бледной кожей и общей слабостью.

Диарея

Симптомы заражения Escherichia coli, продуцирующей токсин шига – штамм, выделенный во время эпидемии в Германии в 2011 году, сходные с симптомами, связанными с энтерогеморрагической инфекцией. Однако чаще наблюдается развитие гемолитического уремического синдрома, который дополнительно сопровождается неврологическими симптомами, которые не обнаруживаются при энтерогеморрагической инфекции.

Симптомы кишечной coli- индуцированной дизентерии, вызванной энтеро-инвазивной кишечной палочкой:

- кровавый понос;

- лихорадка;

- спазмы в животе;

- боль и давление на кишечник при дефекации.

Симптомы диареи путешественников, обычно вызываемой энтеротоксиногенной или энтероагрегационной кишечной палочкой:

- инкубационный период составляет 1-2 дня;

- стул водянистый, обычно не содержит патологических примесей, таких как кровь или слизь;

- сопровождается спастическими болями в животе;

- признаки обезвоживания: сухость слизистых оболочек, общая слабость, усиление жажды.

Усиление жажды

Симптомы обычно длятся 3-4 дня и проходят самостоятельно.

Симптомы детской диареи, вызванной EAggEC, EAEC, EPEC:

- стул водянистый, без патологических примесей, таких как кровь или слизь;

- диарея длится до 2 недель и более;

- иногда лихорадка.

Инфекция мочевых путей уропатогенными штаммами кишечной палочки вызывает так называемые дизурические симптомы:

- учащенное мочеиспускание;

- срочность мочеиспускания;

- уретральное жжение.

В запущенных случаях нелеченных инфекций может развиться пиелонефрит, что проявляется, среди прочего, высокой температурой, ознобом, болью в пояснице, тошнотой или рвотой.

Острый простатит также возникает с высокой температурой, ознобом, болью в нижней части живота, а также с болезненностью, отеком и повышением температуры в области простаты.

Симптомы физиологической инфекции Escherichia coli:

- Пневмония. Обычно поражает нижние доли и может быть осложнена эмпиемой. Симптомы пневмонии: повышение температуры, одышка, учащенное дыхание. При физикальном обследовании выявляются аускультация и приглушенный звук во время постукивания во время аускультации легких.

- Перитонит. Типичное осложнение, которое возникает после разрыва или дивертикула придатка – перитонит. Основные симптомы: лихорадка, сильные боли в животе, а также остановка газов и стула. Физикальное обследование показывает перитонеальные симптомы, в том числе симптом Блюмберга, больной лежит характерным образом – с согнутыми ногами, мышцы живота очень напряжены.

- Заболевания желчного пузыря. Симптомы острого холангита и холецистита: лихорадка с ознобом, боль в животе в правом подреберье и желтуха – симптомы, которые образуют так называемые Триаду Шарко.

Штаммы Escherichia coli, содержащие антиген K1, могут проявляться менингитом у новорожденных, в том числе лихорадкой, желтухой, снижением аппетита, апноэ, рвотой, сонливостью, судорогами. У детей старше 4 месяцев также может возникнуть ригидность затылочных мышц, то есть невозможность пассивного изгиба головы к груди.

Если вы заметили симптомы, описанные выше, обратитесь к врачу.

Как врач определяет диагноз?

Диагностика инфекции Escherichia coli возможна с помощью посева микробиологической культуры или прямого исследования биологического материала, например, фекалий, мочи, крови, мокроты, спинномозговой жидкости, аспирата. Можно идентифицировать штамм, который вызывает инфекцию, а также обнаружить токсины шига.

В зависимости от штамма и места заражения дополнительные анализы показывают наличие лейкоцитов в кале, моче, спинномозговой жидкости, высокие значения воспалительных параметров: С-реактивный белок, прокальцитонин, фибриноген. Для диагностики пневмонии назначается рентген легких, а компьютерная томография для внутрибрюшных инфекций.

Рентген легких

Методы лечения инфекционных заболеваний, связанных с кишечной палочкой

Основой для лечения диареи, вызванной инфекцией кишечной палочки – гидратация организма.

Применение антибиотиков, как правило, не является необходимым. Более того, антибиотики противопоказаны при лечении штаммов, продуцирующих токсины шига, в связи с повышенным риском развития гемолитического уремического синдрома. Также увеличивают этот риск противодиарейные препараты, блокирующие перистальтику кишечника, такие как лоперамид.

Инфекции, вызванные другими штаммами кишечной палочки, требуют антибиотикотерапии. Иногда необходимо хирургическое лечение, дренирование абсцесса или искусственная вентиляция легких с помощью респиратора.

Искусственная вентиляция легких с помощью респиратора

Можно ли полностью вылечить инфекции, вызванные кишечной палочкой?

Прогноз полного выздоровления зависит от вовлеченных органов, серьезности инфекции и времени, когда было начато лечение.

В некоторых случаях кишечная палочка выделяется из фекалий здоровых людей даже через несколько недель после исчезновения симптомов. У детей период носительства обычно длится дольше, чем у взрослых.

Гемолитический уремический синдром, осложняющий инфицирование штаммами, продуцирующими токсин шига, связан со смертностью в 2-3% случаев, в то время как неонатальная септицемия, вызванная штаммом Escherichia coli K1, связана с 8%-ным риском смерти.

Что делать после прекращения лечения кишечной палочки?

Пациентам с менингитом может потребоваться реабилитация и последующее наблюдение для выявления неврологических дефектов. Лечение после других инфекций рассматривается индивидуально.

Что делать, чтобы избежать инфекций кишечной палочки?

Чтобы избежать энтерогеморрагической инфекции кишечной палочки, тщательно мойте руки после посещения туалета, смены подгузников, перед приготовлением пищи, после контакта с животными.

- Готовьте мясо таким образом, чтобы оно было полностью проварено;

- Избегайте сырого непастеризованного молока и молочных продуктов;

- Также не употребляйте непастеризованные соки;

- Избегайте глотания воды при плавании в озерах, прудах, бассейнах.

Рекомендации по профилактике «диареи путешественников» включают:

- Соблюдение гигиены, в том числе частое мытье рук с мылом или использование спиртовых средств, особенно перед едой;

- Питье только бутилированной, кипяченой или химически очищенной воды, без использования водопроводной воды и льда, приготовленного из воды неизвестного происхождения;

- Использование бутилированной, кипяченой или химически очищенной воды для мытья посуды, полоскания рта, мытья фруктов и овощей, приготовления еды и кубиков льда;

- Употребление продуктов в фирменной упаковке или свежеприготовленных в горячем виде.

- Не есть сырое мясо и морепродукты, а также неочищенные фрукты и овощи.

Поделиться ссылкой:

Источник